Home » Meteorites » Types of Meteorites

Illustration by Timothy Arbon

Illustration by Timothy Arbon

METEORITE TYPES AND CLASSIFICATION

The second in a series of articles by Geoffrey Notkin, Aerolite Meteorites

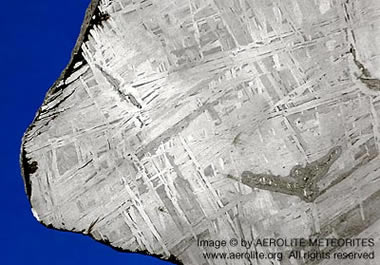

Iron Meteorite: Detail of a polished and etched slice from a siderite (iron) meteorite found in the Brenham, Kansas strewnfield in 2005 by professional meteorite hunter Steve Arnold. The slice has been etched with a mild solution of nitric acid to reveal an interlocking pattern of iron-nickel alloys, taenite and kamacite. The lattice-like structure is known as a Widmanstätten Pattern after Count Alois von Beckh Widmanstätten who described the phenomenon in the early 1800s. Photo by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

It is often said that when the average person imagines what a meteorite looks like, they think of an iron. It is easy to see why. Iron meteorites are dense, very heavy, and have often been forged into unusual or even spectacular shapes as they plummet, melting, through our planet's atmosphere.

Though irons may be synonymous with most people's perception of a typical space rock's appearance, they are only one of three main meteorite types, and rather uncommon compared to stone meteorites, especially the most abundant stone meteorite group-the ordinary chondrites.

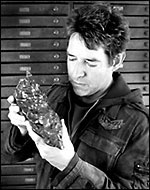

Iron Meteorite: A superb 1,363-gram complete iron meteorite from the Sikhote-Alin meteorite shower which occurred in a remote part of eastern Siberia in the winter of 1947. This fine specimen is described as a complete individual, as it flew through the atmosphere in one piece, without fragmenting. Its surface is covered with scores of small regmaglypts, or thumbprints, created by melting during flight. The Sikhote-Alin shower was the largest recorded witnessed meteorite fall in history. Photo by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

The Three Main Types of Meteorites

Although there are a large number of sub classes, meteorites are divided into three main groups: irons, stones and stony-irons. Almost all meteorites contain extraterrestrial nickel and iron, and those that contain no iron at all are so rare that when we are asked for help and advice on identifying possible space rocks, we usually discount anything that does not contain significant amounts of metal. Much of meteorite classification is based, in fact, on how much iron a specimen does contain.

Stone Meteorite: A 56.5-gram complete individual of the Millbillillie eucrite from Australia. It was a witnessed fall (1960) and is a rare type of achondrite—a stone meteorite which does not contain chondrules. Eucrites are volcanic rocks from other bodies in the solar system, and Millbillillie is one of the very few meteorites which does not contain iron-nickel. Note the glossy black fusion crust, and fine flow lines which were caused as the surface of the meteorite melted during flight. This specimen is also highly oriented, with a textbook snub-nosed leading edge (pictured) and a flat back. Photo by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Iron Meteorites

When I give lectures and slideshows about meteorites to rock and mineral societies, museums, and schools, I always enjoy commencing the presentation by passing around a softball-sized iron meteorite.

Most people have never held a space rock in their hands and when someone does pick up an iron meteorite for the first time their face lights up and their reaction is, almost without fail, to exclaim: "Wow, it's so heavy!"

Iron meteorites were once part of the core of a long-vanished planet or large asteroid and are believed to have originated within the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter. They are among the densest materials on earth and will stick very strongly to a powerful magnet. Iron meteorites are far heavier than most earth rocks-if you've ever lifted up a cannon ball or a slab of iron or steel, you'll get the idea.

In most specimens of this group, the iron content is approximately 90 to 95% with the remainder comprised of nickel and trace elements. Iron meteorites are subdivided into classes both by chemical composition and structure. Structural classes are determined by studying their two component iron-nickel alloys: kamacite and taenite.

These alloys grow into a complex interlocking crystalline pattern known as the Widmanstätten Pattern, after Count Alois von Beckh Widmanstätten who described the phenomenon in the 19th Century.

This remarkable lattice-like arrangement can be very beautiful and is normally only visible when iron meteorites are cut into slabs, polished, and then etched with a mild solution of nitric acid. The kamacite crystals revealed by this process are measured and the average bandwidth is used to subdivide iron meteorites into a number of structural classes. An iron with very narrow bands, less than 1 mm, would be a "fine octahedrite" and those with wide bands would be called "coarse octahedrites."

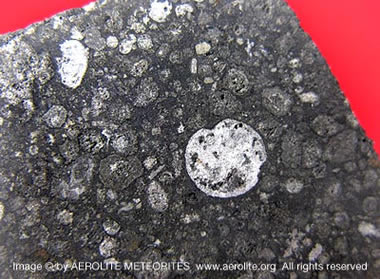

Stone meteorite: Detail of prepared slice of the carbonaceous chondrite Allende, which was seen to fall in Chihuahua, Mexico on the night of February 8, 1969, following a massive fireball. Allende contains carbonaceous compounds as well as calcium-rich inclusions (large white circle near center). NASA scientist Dr. Elbert King traveled to the site immediately following the fall, and recovered numerous specimens which were traded with institutions around the world, making Allende one of the most widely studied meteorites. The Allende meteorite also contains micro diamonds, and is believed to pre-date the formation of our own solar system. Photo by Leigh Anne DelRay, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Stone Meteorites

The largest group of meteorites is the stones, and they once formed part of the outer crust of a planet or asteroid. Many stone meteorites-particularly those that have been on the surface of our planet for an extended period of time-frequently look much like terrestrial rocks, and it can take a skilled eye to spot them when meteorite hunting in the field.

Freshly fallen stones will exhibit a black fusion crust, created as the surface literally burned during flight, and the vast majority of stones contain enough iron for them to easily adhere to a powerful magnet.

Some stone meteorites contain small, colorful, grain-like inclusions known as "chondrules." These tiny grains originated in the solar nebula, and therefore pre-date the formation of our planet and the rest of the solar system, making them the oldest known matter available to us for study. Stone meteorites that contain these chondrules are known as "chondrites."

Space rocks without chondrites are known as "achondrites." These are volcanic rocks from space which formed from igneous activity within their parent bodies where melting and recrystallization eradicated all trace of ancient chondrules. Achondrites contain little or no extraterrestrial iron, making them much more difficult to find than most other meteorites, though specimens often display a remarkable glossy fusion crust which looks almost like enamel paint.

Stony-Iron Meteorite: A sea of gold and orange olivine crystals (the gemstone peridot) lie suspended in a matrix of extraterrestrial iron-nickel in this polished slice of the Imilac pallasite, first discovered in Chile's remote Atacama Desert in 1822. When properly prepared, pallasites are among the most alluring of meteorite, and are highly prized by collectors, both because of their rarity and beauty. Photo by Geoffrey Notkin, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Stone Meteorites from Moon and Mars

Do we really find lunar and martian rocks on the surface of our own planet? The answer is yes, but they are extremely rare. About one hundred different lunar meteorites (lunaites) and approximately thirty Martian meteorites (SNCs) have been discovered on earth, and they all belong to the achondrite group.

Impacts on the lunar and Martian surfaces by other meteorites fired fragments into space and some of those fragments eventually fell on earth. In financial terms lunar and Martian specimens are among the most valuable meteorites, often selling on the collectors' market for up to $1,000 per gram, making them worth many times their weight in gold.

| Hunting Pallasite Meteorites |

| Geoffrey Notkin has written extensively about meteorites and has been involved in television documentaries about them. He searched for pallasites with Steve Arnold in Kiowa County, Kansas and iron meteorites and pallasites near Glorieta, New Mexico in an episode of Cash and Treasures. Again, with Steve Arnold, he searched for Brenham pallasites in an episode of Wired Science for PBS. |

Stony-Iron Meteorite: The mesosiderite Vaca Muerta shows characteristics of both iron and stone meteorites, hence its class—a stony-iron. This weathered fragment was found in Chile's Atacama Desert. One face has been cut and polished to reveal a mottled black and silver interior. Photo by Leigh Anne DelRay, copyright Aerolite Meteorites. Click to enlarge.

Stony-Iron Meteorites

The least abundant of the three main types, the stony-irons, account for less than 2% of all known meteorites. They are comprised of roughly equal amounts of nickel-iron and stone and are divided into two groups: pallasites and mesosiderites. The stony-irons are thought to have formed at the core/mantle boundary of their parent bodies.

Pallasites are perhaps the most alluring of all meteorites, and certainly of great interest to private collectors. Pallasites consist of a nickel-iron matrix packed with olivine crystals. When olivine crystals are of sufficient purity, and display an emerald-green color, they are known as the gemstone peridot. Pallasites take their name from a German zoologist and explorer, Peter Pallas, who described the Russian meteorite Krasnojarsk, found near the Siberian capital of the same name in the 18th Century. When cut and polished into thin slabs, the crystals in pallasites become translucent giving them a remarkable otherworldly beauty.

The mesosiderites are the smaller of the two stony-iron groups. They contain both nickel-iron and silicates and usually show an attractive, high-contrast silver and black matrix when cut and polished-the seemingly random mixture of inclusions leading to some very striking features. The word mesosiderite is derived from the Greek for "half" and "iron," and they are very rare. Of the thousands of officially cataloged meteorites, fewer than one hundred are mesosiderites.

| Meteorwritings Menu |

Classification of Meteorites

The classification of meteorites is a complex and technical subject and the above is intended only as a brief overview of the topic. Classification methodology has changed several times over the years; known meteorites are sometimes reclassified, and occasionally entirely new subclasses are added. For further reading I recommend The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Meteorites by O. Richard Norton and The Handbook of Iron Meteorites by Vagn Buchwald.

Geoff Notkin's Meteorite Book

|

About the Author

|

Geoffrey Notkin is a meteorite hunter, science writer, photographer, and musician. He was born in New York City, raised in London, England, and now makes his home in the Sonoran Desert in Arizona. A frequent contributor to science and art magazines, his work has appeared in Reader's Digest, The Village Voice, Wired, Meteorite, Seed, Sky & Telescope, Rock & Gem, Lapidary Journal, Geotimes, New York Press, and numerous other national and international publications. He works regularly in television and has made documentaries for The Discovery Channel, BBC, PBS, History Channel, National Geographic, A&E, and the Travel Channel.

Aerolite Meteorites - WE DIG SPACE ROCKS™

| More Meteorites |

|

What Are Meteorites? |

|

Collecting Meteorites |

|

The Vredefort Crater |

|

Mars Meteorites |

|

Meteorite Identification |

|

Meteorite Types and Classification |

|

Stone Meteorites |

|

The Largest Meteorite |

Find Other Topics on Geology.com:

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|